Clean tech: The language of a new economy

After an initial wave of enthusiasm in the early 2000s, “clean-tech” investments slowed significantly at the end of the decade. However, a second wave has begun to gain momentum in recent years, perhaps—according to experts—because there simply is no other alternative for the planet.

According to a report published by PwC, no less than US$60 billion in venture capital was invested in climate tech worldwide between 2013 and 2019. These investments grew at an impressive compound annual rate of 84% and supported no fewer than 1,200 start-ups. For its part, Bloomberg estimates that worldwide investments in the transition to low-carbon power totalled more than $510 billion in 2020.

These telling figures raise a question: what exactly is “clean tech”? Two investors specializing in this sector are helping to shed some light on this.

From clean tech to climate tech

Chanel Damphousse is a Principal and member of the investment team of MKB, a growth equity firm that invests mainly in next-generation energy and transportation companies. She believes that the term “cleantech” can be confusing: “Ten years ago, the term referred mainly to the energy sector and was often used to distinguish capital intensive technologies, for example thin-film solar, batteries and biofuels. Today, efforts focus more broadly on solutions to decarbonize the economy and address the climate crisis, so it would be more accurate to talk about ‘climate tech’.”

Chanel has identified five major areas of investment according to this vision: energy (including renewables, grid services, energy management, etc.), transportation (in particular, electrification, logistics and mobility in the broader sense), materials and chemical composites (including biochemistry and new composites), management of resources and the natural environment (tailings treatment, carbon capture and storage, etc.) and, lastly, farming and food production (new production and distribution approaches, plant-based meat alternatives, etc.).

She says that “the business model that our society has been pursuing for more than 100 years—with massive industrial investments in technology with a high carbon footprint and, generally, fairly little innovation—is broken.” In her view, making the transition to a low-carbon economy is a gigantic investment opportunity, particularly if it leverages the digital innovativeness of entrepreneurs. “The changes that are occurring are systemic and governments and businesses alike are realigning their priorities to decarbonize processes as well as the economy in general. The pace of innovation has seen considerable acceleration in recent years.” In this context, while traditional economy giants—for example oil producers—are important investors in this transition, venture capitalists play a key role as well: “Our expertise is predicated on helping companies scale and taking them to the next level—this is where we excel and how we contribute to the equation.”

Chanel Damphousse believes that, although the most recent wave of investment could slow down, particularly if accessing capital through public markets becomes harder, investing will remain strong and continue to grow. “2020 was a breakthrough year for climate tech, and there is no turning back. The transition to a lower-carbon, more digital and more efficient economy is on its way”.

Simply the new way of doing things

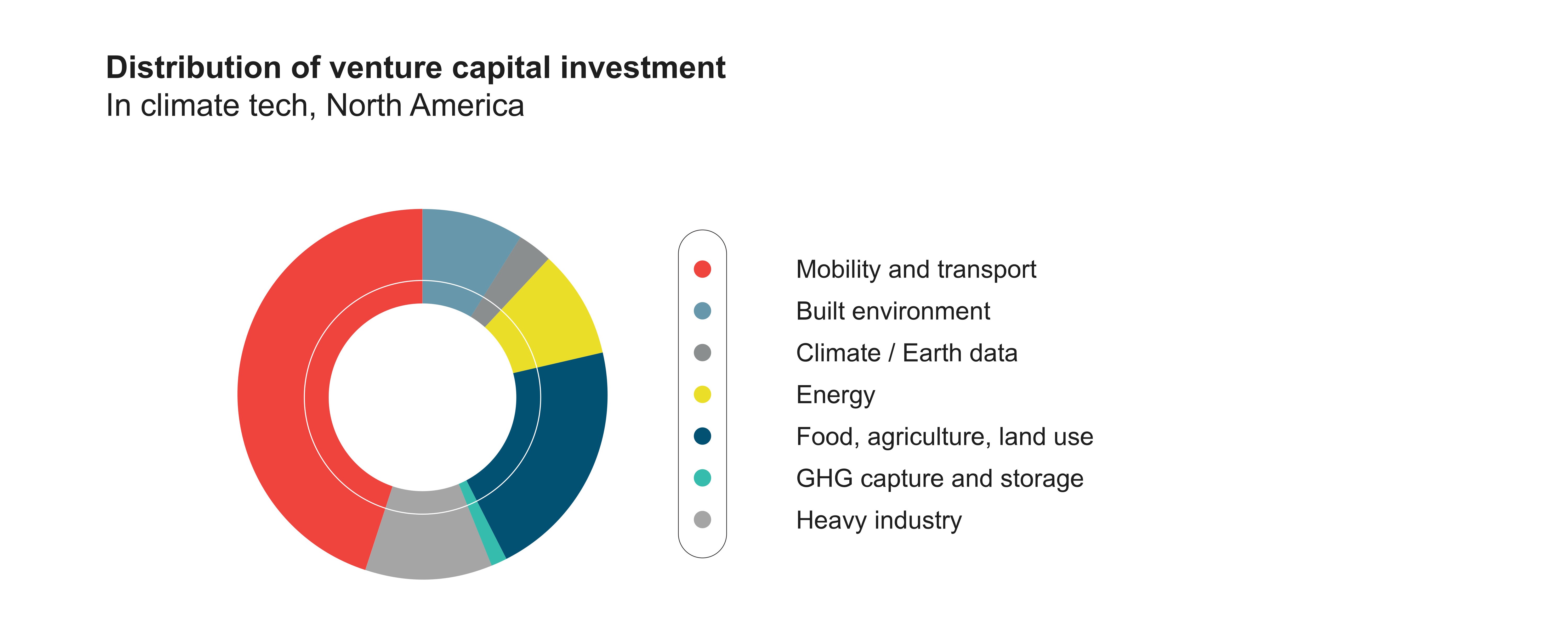

The U.S. and Canada account for nearly half of worldwide investment in climate tech start-ups, with nearly half of capital being invested in companies focussing on transportation and mobility initiatives, followed by the farming, food production and land management and energy sectors.

It is precisely these three industries that are the priority for Spring Lane Capital, whose Managing Partner and Co-founder is Christian Zabbal. Like Chanel Damphousse, he believes that the term “clean tech” has lost some impact because it is no longer sufficiently precise. “What we’re really talking about is a global transition to a world where infrastructure will be more decentralized, more digital and less carbon intensive. It’s simply the new way of doing things.”

Christian believes that the transformation under way will not stop since there is no viable alternative to a decarbonized world and because there is now a general consensus regarding this vision. “Investors in high-carbon assets are increasingly measuring the associated risk. It took decades to build asset value, and this value is diminishing quickly. They want to rebalance their asset mix to mitigate this risk, which is freeing up capital for low-carbon initiatives.

However, the Managing Partner of Spring Lane, which invests in long-term infrastructure projects among other things, warns against the temptation of assessing everything in terms of digital investment cycles, reiterating that infrastructure projects require substantial capital assets. “Electrons move much faster than atoms. If you start evaluating an infrastructure project based on a Web chronology, there’s no doubt that you’ll be disappointed because it takes time for the world to move all of these atoms to create a new economic model. Your growth curves need to be reasonable. In fact, that may be a difference between the “clean tech” bubble of the 2000s and the “climate tech” wave of the 2020s. We now know that we’ll be playing a long game and that capital investments will be rewarded as long as we’re patient.”

Christian sees a future for Québec and Canadian start-ups as part of these overall changes. “Paradoxically, the availability of low-cost renewable energy in Québec meant that there was no urgent need driving innovation in the energy sector, as was seen in California, for example. However, this reality is changing and a number of start-ups are popping up in the energy sector as well as in other industries, notably the forestry and farming sectors. Most appear to be in the technological development stage and not the deployment stage, and their challenges relate to accessing capital and business networks as well as determining the right strategic targets.

That said, decarbonizing the economy is inherently a global challenge: there is no reason for local start-ups not to set their sights on the international—or at the very least—the Western market.”

The following sources were used for this article: BloombergNEF, Energy Transition Investment Trends 2021; CleanTech Group, Global CleanTech 100, 2021; PwC, The State of Climate Tech 2020; Statistics Canada, SME Profile: Clean Technology in Canada – February 2020.